The recently signed Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (JGTRRA) marks the third major tax-cut package passed by Congress in as many years. This most recent package will prove particularly beneficial to individual investors. However, the plan comes at the cost of additional complexity because some changes are retroactive and all are set to expire. While we defer to your accountant regarding the impact of these changes on your own circumstances, here we highlight some the changes that could impact you significantly.

Marginal Rates

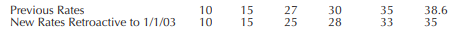

JGTRRA essentially accelerates rate changes previously scheduled for 2006. Investors may wish to reduce the amounts they have withheld from their paycheck, particularly since the changes are retroactive to the beginning of the year. The rates revert to the previous rates after 2010.

The law also raises the taxable income levels for those in the lowest (10 percent) bracket. For single filers the income threshold increases from $6,000 to $7,000, and for married couples it increases from $12,000 to $14,000. In an odd twist, the old 10 percent thresholds will reemerge in 2005, but in 2008 the new thresholds will again go into effect. It is important to understand that taxpayers in all brackets will benefit from this change, as well as from all rate reductions applicable to brackets lower than their own.

Capital Gains

New capital-gains rules have gone into effect as well; new lower rates apply for both regular and Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) purposes. For sales and exchanges of property on or after May 6, 2003, and before December 31, 2007, the maximum net capital-gains tax rate will be 15 percent, down from 20 percent previously, and the 10 percent capital-gain rate for lower-income tax payers will fall to five percent. For 2008 transactions, the 15 percent rate will remain in effect, but for lower-income taxpayers, the five percent rate will fall to zero. After December 31, 2008, the old rates of 10 percent and 20 percent will return.

The 18 percent rate (eight percent for lower-income taxpayers) for property held for more than five years is effectively repealed until January 1, 2009, when the pre-JGTRRA capital gains rates are scheduled to reappear. Not all property will qualify; for example collectibles remain subject to a 28 percent maximum rate.

Dividends

For most taxpayers dividend income from a domestic or qualified foreign corporation will be taxed at the same maximum of 15 percent that applies to capital gains, though taxpayers in the 15 and 10 percent brackets will pay a five percent rate. This is a boon to High YieldDow (HYD) investors. The new rates have already boosted both the demand for and the prices of high-yielding stocks.

Prior to the change, investors in the top bracket who had taxable HYD accounts would have paid $3,860 in taxes on $10,000 in dividends; now they will pay only $1,500, for a reduction of 61 percent in taxes paid. The new rate is retroactive to cover dividends received after 2002 but the rate terminates at the end of 2008. In an odd twist the five percent rate falls to zero at the end of 2007, but the pre-JGTRRA rates return beginning in 2009.

The definition of a “qualifying dividend” will emerge pending yet-to-be-issued rules and regulations. However, it is clear that dividends paid by certain entities, such as Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), which typically pay no corporate income taxes, will not qualify for the lower rates.

Our Take

While investors should generally be pleased by these changes, we do have some concerns. The pre- and post-JGTRRA capital gains rates could create problems. The spread between the highest tax bracket and the capital-gains rate has spread from 18.6 percent to 20 percent. This makes it more tempting to “convert” short-term gains and ordinary income to long-term capital gains, and it could spark the reemergence of heavily promoted and costly tax avoidance schemes.

The dividend tax reduction has sparked some concern that tax-advantaged municipal bonds may prove less popular, resulting in higher financing costs for municipalities. We think this is a stretch. Bonds and stocks are distinct asset classes; dividend-paying stocks are far more volatile than bonds and make a poor substitute.

However, as a result of the compromise on the dividend tax, certain strictures were dropped pertaining to dividends that escaped taxation at the corporate level. In the original proposal any dividends paid that exceeded previously taxed corporate income would not have benefited from the rate reduction. However, the new requirements are not as stringent. We expect greater complexity for investors and corporations alike.

Also in This Issue:

Interest Rates and Bond Risk

Placer Dome

Changes at Vanguard

The High-Yield Dow Investment Strategy

Recent Market Statistics

The Dow-Jones Industrials Ranked by Yield

To access the full article, please login or subscribe below.

Already a Subscriber?

Log in now

Subscribe Today

Get full access to the Investment Guide Monthly.

Print + Digital Subscription – $59/YearIncludes 12 Print and Digital Issues

Print + Digital Subscription – $108/2 Years

Includes 24 Print and Digital Issues

Digital Subscription – $49/Year

Includes 12 Issues

Digital Subscription – $98/2 Years

Includes 24 Issues