Throughout one’s working career and early retirement, an owner of a Traditional IRA faces an opportunity to convert his or her IRA to a Roth IRA. The decision is not black or white and therefore sometimes gets ignored entirely. However, prudent investors with IRA accounts should always keep this technique in mind. The notion merits renewed consideration under historically low federal income tax rates.

Roth vs Traditional IRA

A Traditional IRA allows workers to put aside earnings “pre-tax.” This means that one can initially avoid paying income taxes on earned income (subject to limitations) by contributing such income to an IRA account.Many employer-sponsored retirement plans are similar in principle, including 401(k), 403(b), or SEP IRA plans (upon retirement, many investors choose to convert 401(k) and similar plans to “Rollover” IRAs). When a retiree withdraws funds from a Traditional or Rollover IRA, those funds are 100 percent taxable as ordinary income, just like taxable wages. Retirement withdrawals are mandatory because Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) are imposed beginning at age 72.

A Roth IRA, on the other hand, allows only “after-tax” deposits. This means that contributions are made from earnings that have already been taxed. Employer plans with similar features, such as Roth 401(k) accounts, are now increasingly available. Contributions to a Roth are not tax deductible. Rather, the advantage is that withdrawals in retirement are taken 100 percent tax-free, regardless of size. Moreover, Roth IRAs are not subject to the RMDs that apply to Traditional IRAs. This makes them an ideal vehicle for long-term investing. Many investors designate their Roth IRA as the last account to tap for retirement spending and earmark their Roth assets as an eventual bequest for heirs.

Many workers want to know whether it is better to put money in a Traditional or a Roth account. The difficulty with this question is that the answer depends on current and future tax rates. If your marginal income tax rate is the same during your career as it is in retirement, then there is no difference in “after-tax” value of a Traditional versus a Roth account.

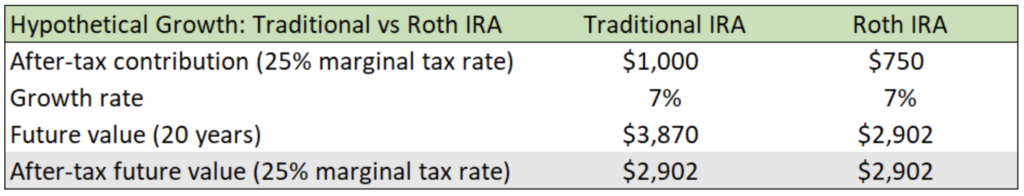

Consider an example. Henry, age 45, earned $1,000 from his employer that he wants to save for retirement (on which he has not yet paid income taxes). His marginal tax rate is 25 percent now, and he expects it to be 25 percent in retirement. The table nearby shows how contributions would grow under both the Traditional and Roth options. It is evident that Henry will be equally well off whether he chooses to save in a Traditional or a Roth IRA.

The only way that we can know whether one option would be better is if we know current and future income tax rates for Henry. Since most investors cannot predict how much they will have in retirement, and tax rates are subject to change, this is unknowable.

Tax Diversification

Clearly future tax rates are a critical unknown when facing the “Traditional versus Roth” IRA decision. In other words, future taxation is a form of risk. Diversification is an invaluable tool to managing financial risk, and taxation is no exception. In essence, by contributing to both a Traditional and a Roth account, an investor can hedge against risk that future tax rates will be higher or lower than today’s rates.

As a rule of thumb, since we do not know which way tax rates will go in the future, it is sensible to hold both Traditional and Roth accounts. But much depends on individual circumstances.

Other Considerations

One reason that many people seem to prefer a Traditional IRA or 401(k) is the assumption that income tax rate will be lower in retirement. There is some evidence that income, on average, tends to be lower whentaxable wages end in retirement.

However, retired investors with large IRA balances may nonetheless find their income to be quite high after age 72, when mandatory RMDs begin. One’s required distribution at any given age is based on the account balance and the taxpayer’s remaining life expectancy. For example, at age 72, the annual minimum distribution is 3.67percent of the IRA balance1, meaning a retiree with $1 million in IRAs would be forced to withdraw about $36,700 and pay taxes on that amount. The required minimum payout rises to 4.96 percent at age 80 and to 8.27 percent at age 90. In turn, a retiree who still had a $1 million IRA at age 90 would be forced to withdraw and pay taxes on about $82,700. This “threat” of a potentially larger-than-expected IRA balance in retirement may push some to hedge this risk by contributing to a Roth IRA instead of a Traditional IRA.

On the other hand, a young worker with a very high current taxable income, who is highly confident that his or her future tax rate will be lower, might emphasize tax-deductible contributions to his employer-sponsored Traditional 401(k) over the Roth alternative.

The good news is that there is flexibility; an early decision to forego a Roth account can be modified later, as circumstances change.

Roth Conversions

Investors can “convert” Traditional IRAs to a Roth status. Investors can elect to affect a conversion by withdrawing money from the Traditional IRA, paying income taxes on it, and placing the after-tax balance in aRoth IRA. Custodians such as Charles Schwab or TD Ameritrade have a simple form for Roth conversions that can be used to elect a tax withholding for this purpose. Alternatively, the taxes due can be paid from an “outside” source (other than the IRA), if such funding is available. Conversions are flexible in that an investor can elect to convert all or just a portion of their IRA.

Conversions should be approached with caution. For example, a younger worker who has no outside source for paying taxes due might be wise to forego a conversion because the amount converted to the Roth may be significantly reduced by current taxes due. The future value of the tax incurred, had it instead grown tax-free in a Traditional IRA, can be quite large.

There is also a timing risk associated with conversions. Roth conversions that take place right before a decline in markets can generate a tax liability on value that no longer exists. In the past, the tax code had permitted retroactive “recharacterizations” that effectively nullified the conversion in order to avoid such an outcome. A recent tax code revision prohibits such recharacterizations.

When deciding how much to convert one should carefully consider applicable tax brackets. It is often advisable to convert only an amount that would avoid pushing you into a higher tax bracket in the current year. For late-career investors and early retirees with little income, this can still allow for a large conversion opportunity.

Consider for example a married, late-career worker who earns $100,000 and files taxes jointly. Current brackets provide for a 22 percent levy on taxable income between $81,051 and $172,750. This means that the worker could convert up to $72,750 of a Traditional IRA at the taxpayer’s current 22 percent tax rate. Although the tax hit today would be painful, the remaining funds would grow tax-free in the Roth IRA without the onus of required minimum distributions. This may turn out to be quite a prudent decision, especially if current tax rates are revised or expire.

Those facing a period of lower taxable income may want to take advantage of a Roth conversion. For example, it is common today for workers to shift part-time work in the years leading up to retirement while delaying Social Security. This period of lower taxable income might create an opportunity to convert an IRA to a Roth while in a lower tax bracket.

Like all financial planning considerations, this decision relies entirely upon an individual’s circumstances. AIS provides complimentary tax analysis to prospective clients. Please contact Luke Delorme at 413-645-3327 or LukeD@americaninvestment.com.